A study in Nature Mental Health suggests that children living in U.S. states with higher income inequality tended, on average, to show very small differences in brain structure and connectivity. Some of these brain measures statistically accounted for a portion of the association between inequality and children’s later self-reported mental health problems.

Led by Divyangana Rakesh of the University of Cambridge, with co-authors Dimitris Tsomokos, Teresa Vargas, Kate Pickett, and Vikram Patel, the study analyzes MRI and questionnaire data from more than 10,000 children in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study and links them to state-level income inequality. The authors interpret these subtle patterns as support for viewing income inequality as a social determinant of young people’s mental health

One of the study’s authors, Vikram Patel of Harvard, described the results to the Kings College London News Center:

“These findings add to the growing literature which demonstrates how social factors, in this instance income inequality, can influence well-being through pathways which include structural changes in the brain.”

There is now substantial evidence that unequal societies have higher rates of mental distress. There is a growing effort in developmental neuroscience to show how social conditions such as poverty and inequality might become “embedded” in the brain. However, this framing can risk suggesting that children who grow up in more unequal places are biologically different or even deficient, as if injustice resides in their brains rather than in the social and economic arrangements around them. It also raises questions about what very small statistical effects in huge datasets can tell us about real children’s lives, and about how best to argue for policies that reduce inequality.

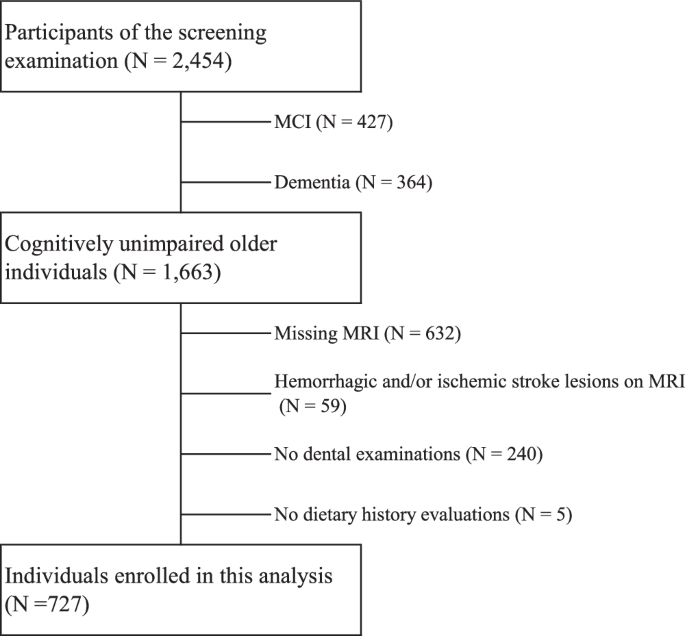

The goal of this study was to better understand potential neural mechanisms by which income inequality might affect children’s mental health. The authors compared neuroimaging and mental health questionnaire data from over 10,000 children ages 9-10 enrolled in the US-based Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study with a state-level index of income inequality (the Gini coefficient) for the 17 states in which the study participants resided.

In the first step, the researchers analyzed neuroimaging data relative to state-level income inequality. They calculated the associations between income inequality (state Gini coefficient) and, individually, 34 brain structure variables measuring cortical thickness and surface area, and 78 variables measuring functional connectivity across 12 brain regions using linear mixed models. They additionally examined total cortical volume, total brain surface area, and average cortical thickness. In a supplementary analysis, they evaluated whether the associations between state-level income inequality and brain structure and connectivity variables varied according to the children’s race/ethnicity.

In the second step, the authors used a statistical technique called mediation analysis to assess whether brain structure and connectivity measures that were statistically significantly associated with income inequality explained any part of the association between inequality and child mental health. These scores were derived from the self-reported Brief Problem Monitor, administered to children enrolled in the ABCD study at their 6-month and 18-month follow-up assessments (the neuroimaging data were collected on participants at baseline, upon enrollment in the study).

Greater income inequality was associated with lower overall cortical volume, average cortical thickness, and total surface area, as well as with lower cortical thickness in the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital regions of the brain. Higher inequality was also associated with altered connectivity within and between various brain networks involved in higher-order cognition.

In the mediation analysis, the authors report a statistically significant indirect effect of higher income inequality “through” lower total surface area, lower cortical volume, and higher dorsal attention network-default mode network connectivity on more self-reported mental health problems among the children in the study.

“These findings indicate that income inequality may shape brain development in a diffuse and pervasive manner, potentially influencing a wide range of cognitive, emotional and behavioral outcomes in children and adolescents.”

The key limitation of this study lies in the disconnect between statistical significance and the biological or clinical significance of quantitative research findings. Statistical significance (indexed by p-values and confidence intervals) captures the precision of the effects estimated from a model; a larger number of observations from a larger number of study participants, for example, will improve the precision of the effect estimates regardless of the clinical meaning of the effects.

In this study, the effects reported are very small. With more than 10,000 participants, it is not surprising that even these small effects are statistically significant, i.e., precisely estimated, yielding p-values < 0.05 even after (appropriate) correction for multiple comparisons. For example, in the first part of the analysis, the authors report an association between inequality and total brain surface area as a regression coefficient of -2.99, with corresponding p-value < 0.001. This means that each unit increase in the Gini inequality coefficient corresponds to an approximately three-unit decrease in total brain surface area.

The authors do not explain what the unit brain surface area is measured in (likely square centimeters or millimeters), but Figure 1 of the manuscript shows that the total brain surface areas among the study participants range from below 160,000 units to over 240,000 units. The important question here is not whether the effect (a 3-unit decrease) is statistically significant; the important question is whether a 3-unit decrease is meaningful from a functional or clinical perspective relative to total brain surface area.

Indeed, Figure 1 shows a slight, almost imperceptible decrease in average brain surface area across Gini values from 0.42 to 0.52. The achievement of statistical significance, an artifact of the size of the study sample, should not eclipse the fact that the effect is five orders of magnitude smaller than the smallest brain surface areas in the study population.

The same is true of the results of the mediation analysis. For example, the authors report the portion of the effect of income inequality that is mediated by total brain surface area as (regression coefficient) -0.122, p-value < 0.001. Again, a highly precise estimate of an extremely small and potentially meaningless effect. The interpretation here would be that a unit increase in inequality mediated by brain surface area is associated with a 0.12-unit decrease in the total problems raw score of the Child Behavior Checklist component of the Brief Problem Monitor. The scores on this component range from 50 to 80; again, it seems doubtful that the effect of one-tenth of a point corresponds to a meaningful clinical difference in child mental health.

In many cases, statistical abstractions used in the inference process (such as t-statistics) are presented as results in their own right, even though these quantities lack any inherent meaning, and are interpretable only in the context of the strong assumptions required by the complicated modeling strategies the authors employ.

The authors’ hypothesis, that experiences of inequality can “get under the skin” and activate stress pathways that can alter brain structure and function and result in poorer mental health, is a plausible one. Their forceful arguments for interventions at the policy level to reduce inequality, such as progressive taxation and improvements to social safety net programs, are welcome, appropriate, and would almost certainly have a beneficial effect on youth and adult mental health. However, caution must be taken to avoid overburdening modest quantitative findings with interpretation, and these results occasion further reflection on whether quantitative population research is the most efficacious or effective means by which to advocate for more equitable social policy. Do we need statistically significant quantitative estimates to confidently argue for reducing inequality and improving the material conditions of children and adults?

This question is especially salient in light of previous work covered in Mad in America. This work documents the extensive body of research linking adverse social conditions, including income inequality, to altered brain function and worse population mental health. One 2022 study documented a heavy burden of adverse social determinants of health on psychiatric service users in New York City, a 2019 review article critically surveyed emerging research into so-called “neural phenotypes of poverty,” and Mad in America has also reported on research linking social inequalities to increased mental distress during the Covid-19 pandemic.

A 2018 book, The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity, and Improve Everyone’s Wellbeing anticipated the study authors’ mechanistic hypothesis – that greater inequality increases stress by creating and exacerbating social divisions and competition, and a study in the Lancet from the previous year linked higher income inequality to greater susceptibility to depression at the individual level.

The results of the present study provide modest supplemental support to this developing consensus around the deleterious mental health effects of inequality; future research should go beyond demonstrating statistical significance to evaluating clinical or qualitative meaning in order to advocate for interventions likely to be effective in reducing social inequalities and improving mental health.

****

Rakesh, D., Tsomokos, D. I., Vargas, T., Pickett, K. E., & Patel, V. (2025). Macroeconomic income inequality, brain structure and function, and mental health. Nature Mental Health, 1-13.

link

+ There are no comments

Add yours